MIKHAIL ROGACHEV

Historian, editor of multivolume collection Repentance: The Komi Republic’s Martyrology of the Victims of Political Repressions

Rally near the chapel commemorating victims of political repressions in Syktyvkar

I came to Memorial out of curiosity. My friends told me there was going to be a coordination meeting, and, well, I got interested and decided to come. I am a historian after all. I did not have any personal motives. There were no victims of political repressions in my family. Revolt Ivanovich Pimenov, the first chairman of the board, nominated me as a candidate for the deputy chairman’s position. Since then, it was all plain sailing — people started coming, telling their stories, asking to help with rehabilitation. All this gave rise to a feeling that it was not enough to simply know this subject yourself, it was important to be able to explain it to others, logically, without sloganeering.

Our martyrological collection is not just a name list. It is a document. For many it is also the last record about their relatives. I have never counted how many people came to us, but it was a lot. People find familiar names in the books, they ask to find out what happened to the person, where he or she could be buried. And the best we can do is to point at some location, where the cemetery was. The graves cannot even be found.

Prisoners at the construction site of Kotlas-Kozhva railway, 1940. From the collection of the National Museum of the Komi Republic

Every volume of our martyrology is issue-related. This makes our publications unique. Each volume is dedicated to the memory of a certain group of former political prisoners. There are volumes about political prisoners in the Komi Republic, about Russian Germans; there is a separate volume about dispossessed deportees from the whole of Russia. Another one looks at Poles, who were deported to this territory. There is a volume about Ukhta-Pechora Labor Camp prisoners and a separate publication about Ukhta-Izhma Labor Camp. We wanted to publish a brand new edition dedicated entirely to Vorkuta, but we could not make this happen yet.

We are working on an encyclopedia «The Gulag in the Komi Republic.» Prisoners’ biographies constitute one half of the text. Another half covers camp labor, newspapers, theatres, and the settlements that have grown out of camps. More than 700 entries are ready by now. There are no other books like this one. It is unique.

«The Gulag is an essential part of our history which is still being written. We are talking about the fates of millions of our citizens who went through this.»

All the talks about the scale of Stalin’s repressions, about the numbers, about who is lying and who is not, are just froth until we count exactly how many people convicted under the article 58 went through labor camps. Interestingly, 90% of all political convicts were people who had nothing to do with politics. They were ordinary workers and peasants busted in the heat of the moment.

I had a friend, Tarakanov, who had lived to be a hundred. Sadly, he has passed away recently. He was a big shot in the Executive Comission. He remembered that, when he had been arrested and put in a camp, he asked his cellmate about his charges. His cellmate’s answer was “I don’t know, I was told it’s for some kind of ‘drosism’.” People could not even pronounce “Trotskyism,” let alone understand what it meant!

There was this other case a long time ago. I was talking on the radio about the fate of Vilho Gren, a Finnish worker who came to the Soviet Union to look for a job and ended up in a camp, where he eventually perished. I told that story just to give an example. But they heard this program in Finland. Some journalists got interested; they started looking for that man’s traces. And they found his wife. For the past 50 years she had no idea of what had happened to her husband — he had just left and disappeared.

«There were a lot of outstanding people among the hundreds of thousands of the Gulag’s inmates: writers, poets, scientists, engineers.»

In 1937, “camping” plan for Syktyvkar hit the target, and 2,000 people were put in custody. There were almost no detentions in the villages, because it was quite hard to catch anyone there — it takes about two days on a boat to get to each village, so why bother? During the years of Stalinist purges, 11,000 people in the Komi Republic were convicted under the article 58. 8,000 of those were already convicted inmates, which means they were tried for the second time in the camps.

For 30 years the Gulag determined the development of the republic. From 1930 until 1960, the economy was being supported by convict labor. Oil, coal, and gas were extracted by prisoners; as much as one half of logging companies used convict labor. More than 60 towns of the republic grew out of camp settlements.

Today, we have Russia’s biggest data bank — 130,000 people, which is about 10% of the work we are still intending to do.

«We have been working for fifteen years. During this time, we have collected the figures only on two camps, and there were as many as twenty camps in the Komi Republic alone.»

State archives have recently complicated matters by denying access to personal files to public organizations. Those files are considered to fall under the law on personal data protection, although the dead cannot have personal data, in our opinion.

We often receive help from prisoners’ grandchildren. When we had to pay a 25,000 rubles deposit to participate in the publication tender for the martyrological collection, they helped us raise the required amount. There are always such things in our work.

We have a lot of supporters and some opponents as well. The main argument is «The only thing you want is to muck Soviet history; you only see the bad in it.» «You’re the fifth column working for American ‘cookies’.» Funnily enough, Memorial never received any foreign grants. I am not saying this is good or bad — this is simply a fact.

Our foundation is involved in a lot of things. We not only publish the book commemorating the victims of political repressions, we also collaborate with museums and libraries, and organize exhibitions and conferences. We have up to 20 search teams from schools every summer. They visit the sites of former special settlements and camps, they write down memories, draw plans of these areas, make descriptions, and erect crosses at abandoned cemeteries.

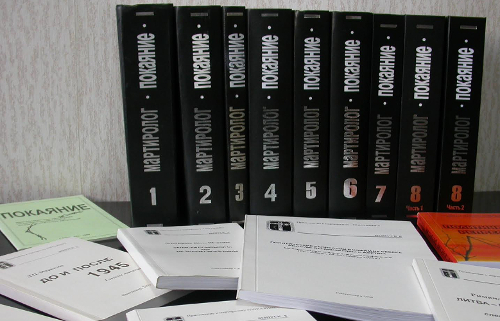

Publications of Repentance foundation

This year we were denied the right to publish our martyrological collection. The university will be handling it from now on; they need it for reputation and money. I do not know how it is going to work. We have not decided what to do next. If nothing changes, it is likely that we will be slowly closing down. It is not that simple. Our library has been transferred to the National Library, where it will be kept as Repentance collection. It is a pity, because initially Repentance was created as a state-public partnership.